Pietro Gaietto

First Paleolithic feminine sculpturines discovered, had the name of "venuses", as it was thought (in my opinion, rightly) that they were corresponding to the feminine ideal of the time.Few years after, these sculpturines have been considered as real "idols" for the fecundity cult, but the name "venuses" has been maintained.

Later in time other opinions linked the Paleolithic "venuses" to the origin of the post-Paleolithic Mother Goddess.

The Mother Goddess is almost always clothed; she is sitting; sometimes, she is showing her breasts; in other areas she is sitting with her dead son on her knees.

There are also who wanted to do a direct link between the representations of the Mother Goddess, and the representations of the Madonna sitting with the dead Christ on her knees.

In my opinion this concept of evolution in the representation of women in a direct line from the Paleolithic to historical times, is too simplistic, because in this path there has been a continuous change regarding religions, with local differentiations in each people, and if a people became more powerful than another, he imposed his own religion, therefore there has been a continuous transformation, different from territory to territory.

Deities always had a practical function in the spiritual field.

For example, in the Ancient Egypt the Goddess Thueris (that I have classified in art between the "humanized animals") had head of hippo and human vertical body with great belly, and was a popular deity much venerated from the pregnant women, and still today considered by the archaeologists as one of the most ancient deities. The Goddess Thueris was not beautiful, and had no attributes of the feminine sex.

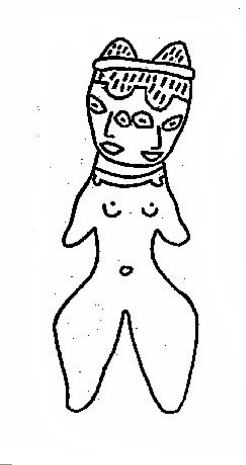

The Mexican "venuses" (Figs. 1, 2, 3) and the "European Paleolithic venuses" (Figs. 4, 5, 6) have evident attributes of the feminine sex, that can be assumed had more effectiveness in the erotic sphere, than in that of the fecundity for the pregnant women.

We must not forget that the man of the Upper Paleolithic who sculpted the naked women was a Homo sapiens sapiens like us, but this is also true for Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

The Australian Aborigines were at a cultural stage similar to that of the European Upper Paleolithic, and among the Aborigines who became part of our civilization, cultured, there are also some who purchase pornographic magazines with naked female.

We know that the Goddess Thueris was a popular deity very loved by the pregnant women, since the same Egyptians have left written this information; instead about the propitiatory function of the fecundity of the Paleolithic "venuses" there are not evidences; therefore, we are still at a supposition level.

In European Paleolithic "venuses", the (religious) attribution linking them to the cult of fecundity, however, is not in contrast with the erotic attribution, as these naked ones could very well excite the male fantasy.

In Christian churches, with Baroque art, paintings abound with nudes, even with strong sensuality, and yet they are all religious subjects. Even Michelangelo's nudes of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, in Rome, were veiled with ad hoc draperies, as evident from the last restoration.

The European Paleolithic "venuses" (Figs. 4, 5, 6) have a strong eroticism, since all the sexual attributes are evidenced, and the woman is depicted in the right age for the sexual activity, and this not disjunct from a "realistic" artistic style.

The "venuses" of Tlatilco (Mexico) (1, 2, 3) are naked, and the eroticism is just alluded; they seem nudes of little girls. The style of representing the body is not "realistic", but has a harmonious elaboration, since the naked body does not correspond to reality, as in the European Paleolithic " venuses", but is invented. The "venusrs" of Tlatilco, like those European, do not have neither hands nor feet; but they have the legs open and a little of arms, thing that has been possible to realize with the ceramics, while it would have been difficult to do in the Paleolithic, working hard stone.

The "venus" of Willendorf (Austria) (Fig. 6) being carved on tender stone represents very thin arms folded across the chest.

The "venuses" of Savignano and Balzi Rossi do not have even a hint of arms.

The "venuses " of Tlatilco have the face with eyes, nose and mouth, which nevertheless is not a face in realistic style, but is an invented face, that is made in a style that was fashionable in that time.

Between the Paleolithic "venuses", the only one with the face (lateral profile) is the "venus" of Balzi Rossi (Fig. 4) (height cm 6), but mouth and eyes are no present, because it would be impossible to do them, given the smallest dimension of the sculpture.

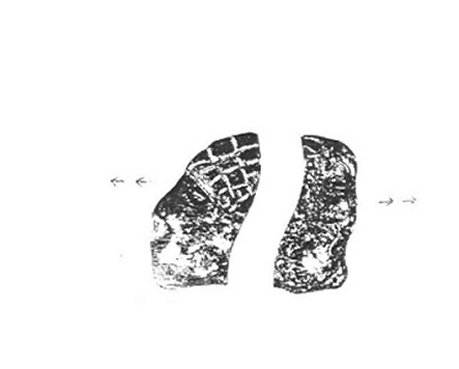

The "Venus" of Savignano (Fig. 5) (height cm 22) has not the face.

The clothing of all these "venuses", Mexican and European, is constituted from headgear and hair. The Mexican "venuses" have necklaces, while European ones don't have it, certainly for technical reasons of depiction, but in Upper Paleolithic the necklaces already existed, since we have found them.

The European "venuses " and those of Tlatilco are not only connected having all headgear and hair styles, but also having two similar types. Let's see the affinities between these two types of outfit.

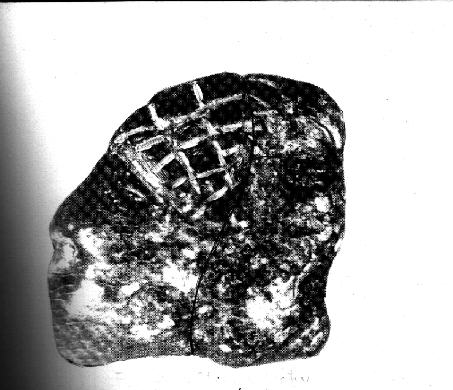

The type probably more ancient is a cone-shaped hair, which is present in the "venus" of Balzi Rossi (Fig. 4) and in the "venus" of Savignano (Fig. 5).

Fig.4 Venus of Balzi Rossi

This type of hair, also interpreted like a pointed hood, is present also in sculptures of heads without body of the Middle Paleolithic of Liguria (see other images in the website of the Museum of the Origins of Man). The components of the artwork, the composition in the representation are always by Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (See on these issues the Museum of the Origins of Man). The hairdress cone-shaped is present in the "Venus" of Tlatilco (Fig. 1) (height cm 6), and also in the bicephalic "venus" of Tlatilco (Fig. 3) (height cm. 11).

Fig.3 Drawing of ceramics statuine

I must underline that these hairs are more realistic than the faces, that is, while the faces are "invented", as they could have been made in a hundred different styles, the hair is made in a realistic way, that is imitative. The faces not are intended to be a realistic portrait, while the hair styles carefully imitate reality, since the ceramic modeling process can allow on statuettes of a few centimeters.

Mine can seem an excess of analysis, but we must consider that face and hair are two distinct representations.

In the European Upper Paleolithic there was an evident distinction, since the face was not represented, and only the hair was depicted. It follows, that this type of outfit was more important than the face. (It is necessary to see in the website of the Museum of Anthropology of Mexico City, or in other websites, the statuines of Tlatilco, in how much drawings are inadequate in evidencing the differences of representation between the faces and the hair styles).

I remember that the statuines of Tlatilco go back to 1.100 - 500 B C.

The second type of hair is found in the bicephalic"Venus" of Tlatilco (Fig. 2) and in the "Venus" of Willendorf (Fig. 6).

Fig.6 "Venus" of Willendorf

This type of hair follows the shape of the cranial cap, and is not pointed, that is cone-shaped.

In the Upper Paleolithic the two types of hair were present simultaneously at the Balzi Rossi, even if probably they have two different origins and, therefore, two different traditions. The hair cone-shaped is found in the "venus" (Fig. 4) and that without cone in the bicephalic head (Fig. 7)

The head of the neandertalian woman has a hairdo called "Nubian style", found also in the "venus" of Brassempouy, instead it is not known that kind of hairdo has the coupled head of Homo sapiens sapiens, however it seems to have thick hair on the forehead.

The hairstyles no cone-shaped , however, are of two types: "Nubian style", which could also be a net on the hair, and that of the " Venus" of Willendorf, which could be a partial or total headgear of pierced shells. To confirm this supposition is a shell cap on the head of the "Young Prince" of the Arene Candide (Finale Ligure, Italy) whose poor remains are held in the Archaeological Museum of Genoa. Finally, it is not to exclude that they were simply combed hair, even if combs, in that phase of the Paleolithic, until now are not known.

Bicephalic "venus" of Tlatilco (Fig.2) is distinguished from the others two here published (Figs. 1 and 3) for having a hair without cone; in this case, it is imaginable that the comb was already of common use. I conclude without concluding, in how much the lines of the evolution do not have neither an origin, neither an end. What is important, for us, are the paths of evolution on the discovered finds.

To the Index

Copyright©2000-2002 by Paleolithic Art Magazine, all rights reserved